The new “history” of the Intel IC is part of a much larger fake “history” written by the Tech Lords to glorify and deify the Tech Lords. The “history” makes a special point of OMITTING the role of IBM. The San Francisco Tech Tyrants vanquished the old Rust Belt tech industry and rewrote the world in their own cool hip Effective Altruist image.

The Great Steve Jobs rewrote the history of computing so it began with The Great Steve Jobs. Everything He touched became a landmark.

In reality computing didn’t begin with Steve. Didn’t begin with Bill Gates. Didn’t begin with Babbage either. Babbage was an interesting dead-end, rediscovered later but not part of the family tree. It certainly didn’t begin with Turing, as New Stalinist is trying to claim this week. Turing’s “tape machine” was invented long after the discipline was well developed. His little abstract Gedankenexperiment didn’t explain anything and didn’t play any part in the development of actual computers. Merely an interesting detour. Much like the number-theory “foundation” of mathematics developed by Hilbert, Peano, et al, which was not a foundation at all, just a tacked-on filigree. Thousands of teachers have ruined millions of students by treating the filigree as a footing.

No, computing began in the dull and obvious location, Herman Hollerith’s 1890 census tabulator. And the functions in that machine are still the dominant functions of modern computers, descended in a direct line from Hollerith. It’s IBM all the way down, with considerable help from DEC and HP and Bell Labs. Steve and Bill contributed hugely in the commercial realm, making the computer seem cool and necessary; but they added nothing meaningful to the technology.

= = = = =

Here’s a simple animation of Hollerith’s 1890 Census machine. This 1890 Tabulator only automated the most tiresome and error-prone stage of the process, counting the holes and sorting cards into ‘pre-programmed’ categories. When you pull the handle of the press, a grid of spring-mounted needles tries to poke through all the hole locations. Where a hole is actually punched, the needle drops through to make contact below, closing a circuit that leads to the corresponding dial above. An electromagnet ratchets the Ones dial forward one step, and the Tens dial follows by reduction gearing. Much like the escapement in a clock.

If this particular combination of holes corresponds to one of the programmed combinations, the Sorter pops an appropriate door open. You’d then take the card, drop it into the one open door, and close the door.

The programming of combinations was done mainly by soldering and unsoldering dozens of wires for each setup! There were a few switchboard-style plugin choices, which would have been like user-selected variables, not like actual software. So my animation is arbitrary, not trying to make any real combinations, showing only that the dials increment and a different door opens for each card.

This process was clearly too ‘manual’ even by the standards of the time, with humans performing several steps that were easily mechanized. After 1890 Hollerith went commercial and quickly developed various ways to feed and read cards automatically, then carry them into appropriate slots. He also began to add more calculation and programming abilities.

The animation doesn’t include the first step: Cards were punched using a pantograph machine, or by hand, to register the information from the handwritten census forms. One card for each person, with labeled hole locations for male, female; child, adult; white, colored; renter, owner; and so on.

Hollerith borrowed the punch idea from an early use of biometrics on Mississippi steamboats. Tickets contained a list of descriptors: race, gender, height, facial hair, etc. The conductor punched the passenger’s description at boarding, then the passenger could reboard at various ports without having to pay a new fare.

He borrowed the sorting idea from Mergenthaler’s Linotype, which was a fresh invention at the time. A Linotype’s font is a huge flat metal cartridge divided into columns, with each column carrying a stack of molds for one letter. When you hit a key, a gate opens on the appropriate column and drops one mold onto the end of the Line-O-Type that you’re building. When the line is done, the machine injects lead into the clamped-together molds to form one slug, which will then print one line in the resulting form. After the injection, the molds are conveyed up to the top of the font, where they are carried across the top of the columns. Each mold has a distinct pattern of slots on its sides, and it drops into the correct column when the slots match the ‘keyhole’ for that column.

And Hollerith borrowed most of his circuitry from telephone switchboards and hotel annunciators, which used drops to indicate a call from one phone or room.

No theory in his inspiration, just steam, lead and iron.

= = = = =

Okay, we ain’t got theory. What else ain’t we got? We ain’t got computing in the usual sense of the word. No math, no Babbage, no Turing.

What do we got? We got pattern-matching and counting and recording. And that’s what computers have been doing, from 1890 to right now. Computers are organizers with secondary abilities to calculate. Example: the latest version of my interactive courseware that I finished and sent off yesterday. The C++ source code contains about 13000 non-comment lines, of which only 120 are explicit arithmetic. In other words, only 1% of the action is adding, multiplying, sines, arctans, etc. The other 99% is pattern-matching and counting and recording. The program presents an image or a text question; waits for a click on some part of the image or a button; increments the number answered and number correct; and holds the results in a file.

Just like the 1890 census. Present a question, wait for the answer, check against patterns, increment counters, drop result into a file.

And sort of like something else … trying to remember …. Aaah yes. Like clover!

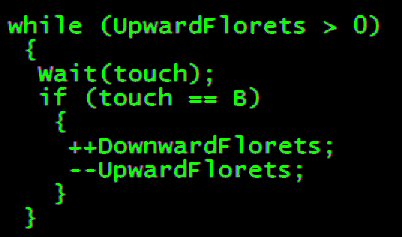

The clover blossom implements the following Legume++ code:

The intelligence is all in the design.

A later system of purely manual sorting was more precisely analogous to the Linotype matrix-sorting method. McBee cards or edge-notched cards came with a set of round holes on all sides, close to the edge. Schools and colleges used them heavily in the ’50s and ’60s.

You could have McBees printed for your use, or simply use one ‘template’ card that indicated the meaning of the holes. You’d type or handwrite a set of info on each card, then use a special triangular edge-punch tool to ‘open up’ a notch into appropriate holes. Sorting them was fun: you’d put a stack in a special box, then insert rods into the holes you wanted. If you wanted info on all the 8th graders in Mr Dillon’s classes, you’d put a rod through the 8th grade hole AND a second rod through the Dillon hole in the stack, using the template card to locate the correct holes. Pull up both rods together. The cards that had been notched for both 8th Grade AND Mr Dillon would fall off the rods and stay in the box, and you could then use them.

= = = = = END 2012 REPRINT.